Notable People:

Mirza Mehdi Khan Etemad-ed-Dowleh Monshi-ol-Mamalek Esterabadi

Mirza Ahmad Khan Motazed-Dowleh Vaziri

Mirza Abdollah Khan Meshkat-ol-Molk Vaziri

Mohandess Mirza Abolghassem Khan Motazed-Daftar Vaziri

In Farsi:

صفحات مربوط به خاندان وزیری در کتاب تاریخ کرمانشاهان

خاطرات علی اصغر خان از نقش خانواده وزیری در انقلاب مشروطیت

میرزا مهدی خان استرآبادی

میرزا احمد خان معتضدالدوله وزیری

Mirza Mehdi Khan "Etemad-ed-Dowleh" "Monshi-ol-Mamalek" -Kawkab- Esterabadi (or Astarabadi)

میرزا مهدی خان استرآبادی اعتمادالدوله منشی الممالک

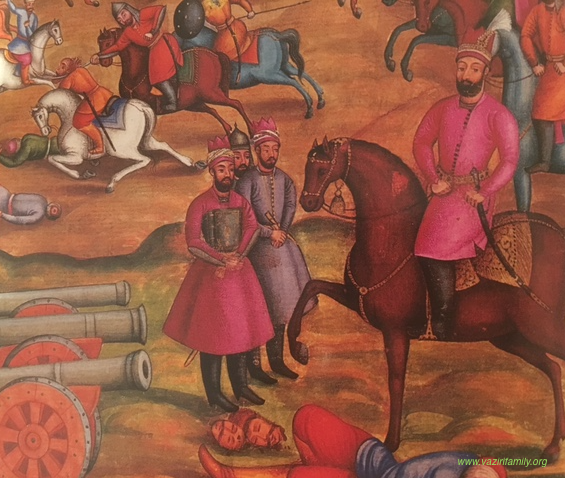

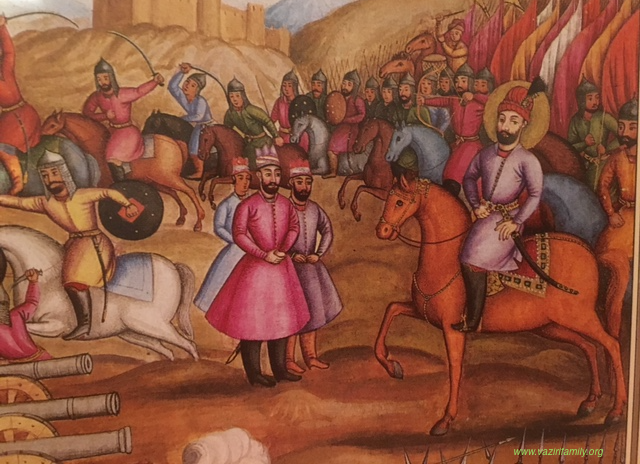

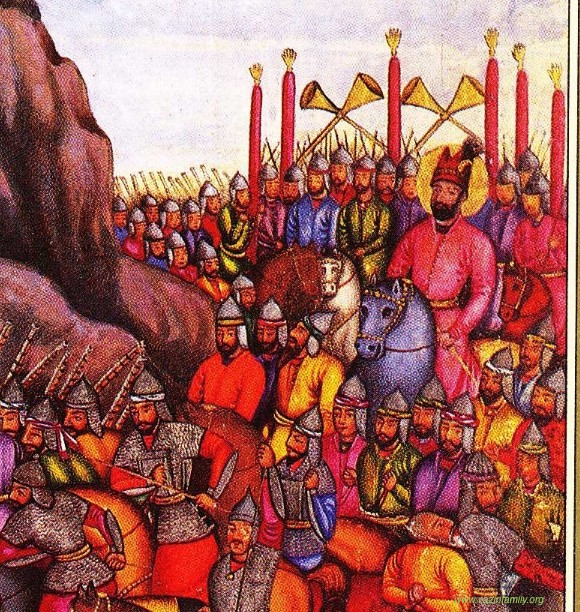

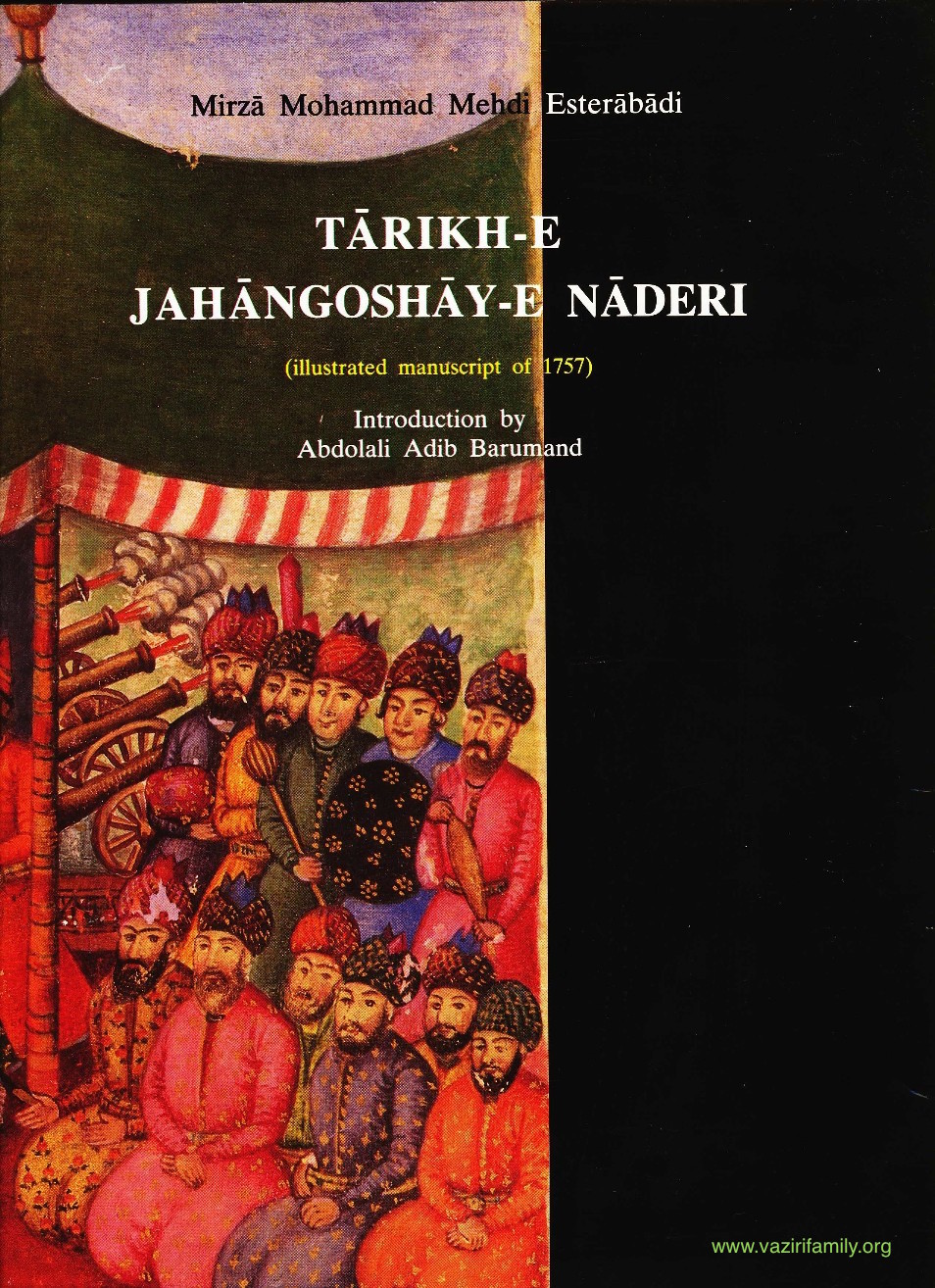

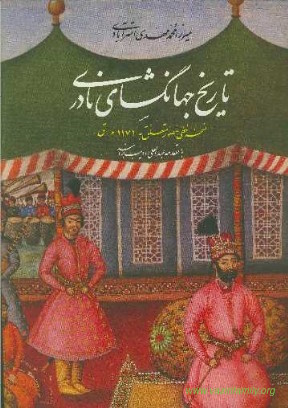

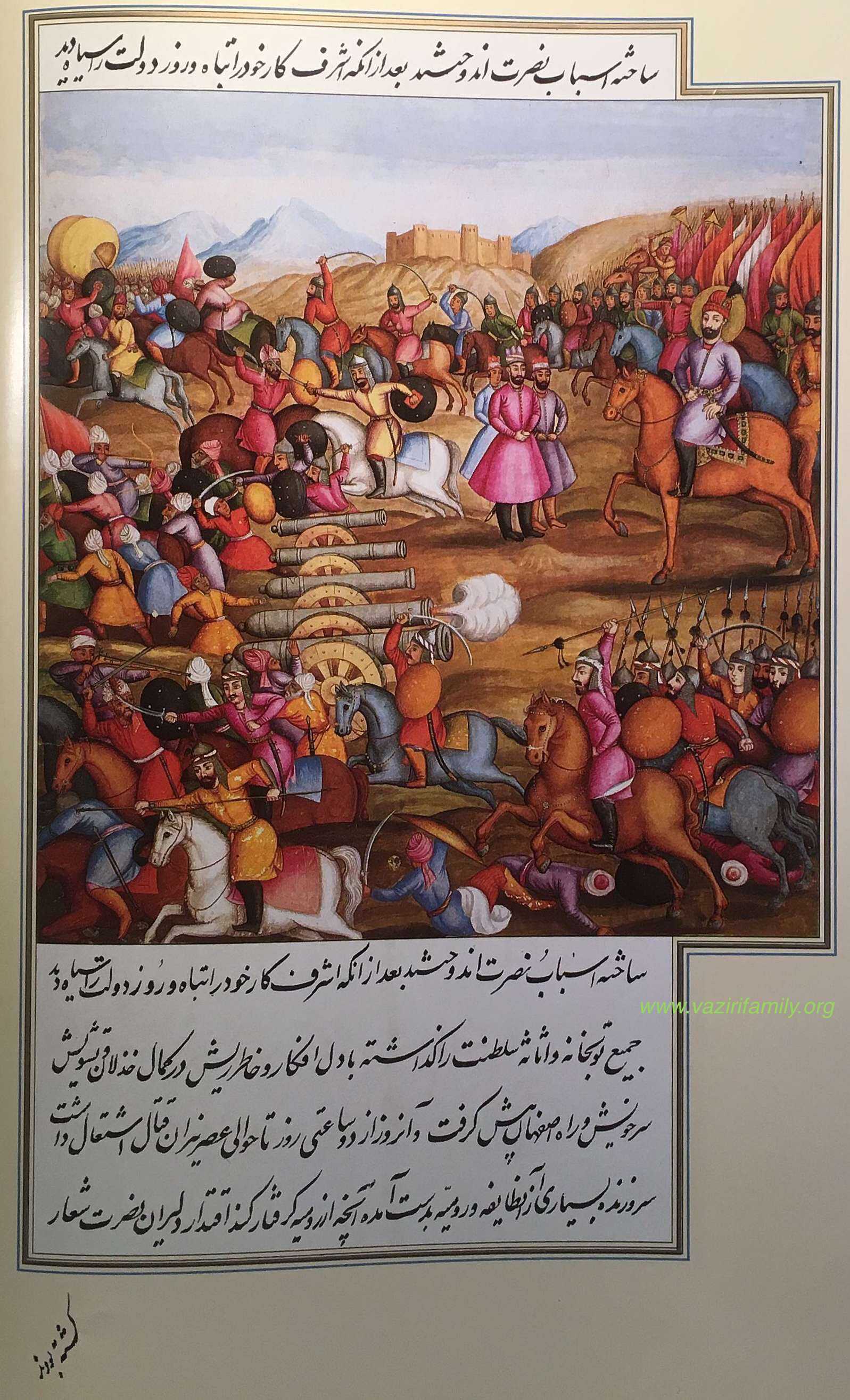

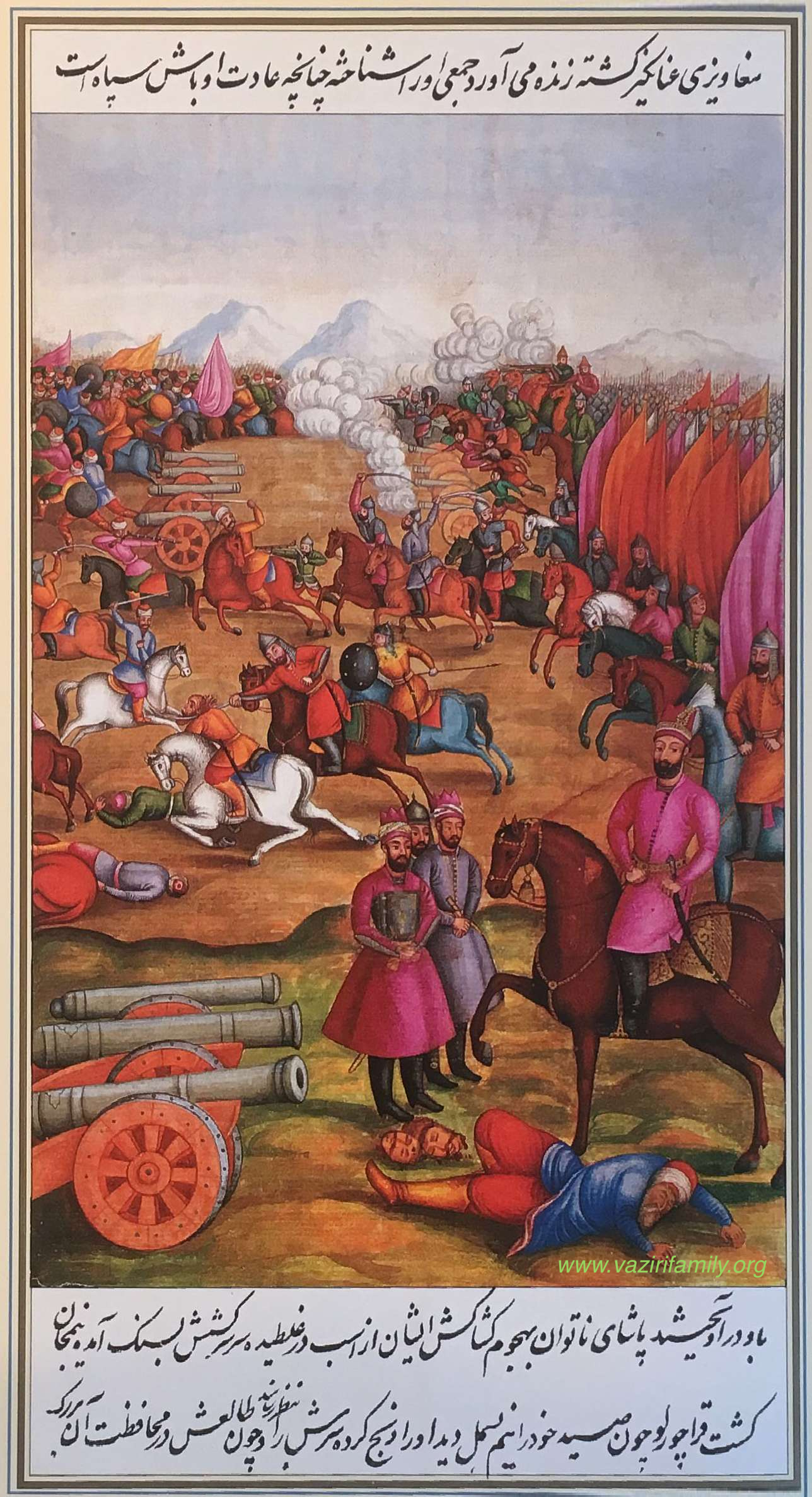

The scenes were painted by an official court painter who accompanied Nader Shah during his battles. Research carried out by Mardis Oven, a British connoisseur of Persian miniature paintings, and several other art connoisseurs in Iran, England, France, the United States, and Turkey have revealed that, so far as the history, style, and themes of paintings are concerned, no other illustrated manuscript similar to this one has been found.

The first painting shows the campaign between Nader and Abdollah Pasha, the Ottoman general. The Persians have defeated the Ottoman army, and the corpse of Abdollah Pasha is on the ground at the feet of Nader’s horse. The person standing against Nader Shah with a book against his chest is Mirza Mehdi Khan.

The second painting shows the campaign between Nader and the Afghans in the desert of Moorcheh Khort, Isfahan. The Afghans are fleeing before Nader’s troops. Nader is on horseback, and three persons are standing in front of him; the person on the left is his son Nasrollah Mirza, and the person in the middle is Mirza Mehdi Khan.

Mirza Mahdi Khan Esterabadi (or Astarabadi) (d. 1760) was the chief secretary (monshi-mamalek), court historian, biographer, grand vizier (etemad-dowleh), foreign minister of Nader Shah Afshar (1698-1747).

Mirza Mohammad Mehdi Khan Etemad-ed-Dowleh Monshi-ol-Mamalek (two honorific titles meaning “the trust of the State” and the “secretary of the countries”) Kawkab (a nickname that he used in his poetry) Esterabadi (sometimes also spelled “Astarabadi”) was born in the seventeenth century in Esterabad (current day Gorgan), a prominent town in northern Persia, to Mirza Nassir Khan Esterabadi, an important bureaucrat in the region.

He spent his youth working in the Safavid dynasty’s court as a scribe until the Afghans invaded Persia in 1722. Nader Khan, a young colonel at that time, fought against the Afghans, and Mirza Mehdi Khan supported him. Thanks to his support, Mirza Mehdi Khan became the official court historian, strategist, advisor, confidant, friend, and chief secretary of Nader Shah Afshar. He was given the title “Monshi-ol-Mamalek” (equivalent to foreign minister at that time).

When the Ottomans were beaten in 1739, Mirza Mehdi Khan and Mostafa Khan Shamlou were appointed as the ambassadors of Persia in the Ottoman Empire. That same year, Nader Shah was assassinated, and the two ambassadors went back to Persia with their army to try to put a Safavid prince on the throne, but they were defeated by Karim Khan Zand. Esterabadi spent the last years of his life writing books and poetry.

He wrote the famous History of Nader Shah (Histoire de Nader Chah, Tarikh-e-Jahangoshaye Naderi), which is the main source of the history of Nader Shah and his conquests.

Esterabadi died sometime between 1759 and 1768 (see Lockhart, Nadir Shah, p. 294 n. 1).

The campaign of Herat. Nader Shah sits on the horse, and Mirza Mehdi Khan stands in red clothes in front of him.

Mirza Mehdi Khan is known as a prominent intellectual and author of his era. Besides the History of Nader Shah in 1757, he also wrote the books Durra-yi Nadira and Sanglax, a Persian guide to Turkish language in 1757, which was the first Persian-Turkish dictionary. The dictionary includes an introduction by Sir Gerald Clauson.

In 1740, he was also charged with translating the gospels into Farsi, which led to the first written Bible in Farsi (refs. 2 and 16).

In 1768, King Christian VII of Denmark visited England and took History of Nader Shah with him. He asked Sir William Jones (1746–1794), an orientalist and specialist in the history of old India, to translate it into French. This, in turn, led to the publication of Histoire de Nader Chah in 1770. The book was also the subject of a study led by the United States Naval Academy in 1996.

Sir William Jones also wrote a foreword to the Histoire de Nader Chah in French (please scroll down for English):

"PREFACE à la traduction Françoise.

CET Ouvrage n’est point entiérement inconnû; un* Auteur Anglois, dans l’agréable récit de ses voïages, a fait mention d’une vie de NADER CHAH, écrite en Persan; mais, il ajoute, qu’il est peu probable qu’elle paroisse jamais en Europe. En effet, pour que le public fût enrichi de ce rare présent, il a fallû que le destin le fit tomber entre les mains d’un Roi distingué par son amour pour les Belles Lettres, & par la délicatesse de son goût; ce qui n’étoit pas un bonheur facile à prévoir. Chargé par les ordres de ce Monarque de traduire & de publier ce manuscrit, je desirerois de mon côté pouvoir satisfaire le lecteur, en lui donnant une parfaite connoissance de l’auteur que je traduis; mais, mes recherches à cet égard aïant été vaines, il faut qu’il se contente de mon opinion. J’avoüe d’abord, que je ne suis pas de l’avis de l’écrivain que je viens de citer, qui annonce mon auteur comme un général ou un commandant; il me paroit plutôt un homme d’un savoir profond, d’une éloquence agréable, & parfaitement versé dans la litérature orientale, ainsi que dans la poësie de son païs. Ses notions sur l’art militaire, la maniére dont il décrit les batailles ne conviennent nullement à un guerrier; elles s’accordent bien mieux avec le titre de Mirza, qui signifie homme d’étude, lorsqu’il précede le nom propre; celui de Khan, qui s’y trouve joint, prouve seulement que le savoir, en Asie, est le chemin de la fortune, aussi bien que celui de la gloire. Comme il n’y a que douze ans que cette histoire a été écrite, il est probable que Mirza Mohammed Mahadi Khan de Mazenderan vit encore, à moins qu’il n’ait péri dans quelque danger semblable à ceux qu’il décrit, & qui étoient si frequens dans sa patrie aux tems malheureux qu’il déplore: cependant le récit de ces rebellions perpétuelles, souvent compliquées, & renouvellées aussitôt qu’appaisées, a quelque chose de sec & de fatiguant. L’auteur l’a senti lui-même; ainsi, lorsqu’il n’a pas eû des événemens grands & frappants à raconter, il a tâché de faire supporter la minutie, & même quelquefois l’obscurité, de sa narration par des morceaux de poésie Persanne aussi bien choisis que placés. Ces essais de Rhétorique orientale sont sur tout admirables dans les descriptions variées du printems, qu’il donne au commencement de chaque année, & dans lesquelles, en géneral, il fait allusion à ce qui s’y est passé de plus remarquable. Cet ouvrage doit naturellement intéresser le public, & attacher le lecteur; les faits en sont si récens, qu’ils ne sauroient être effacés de notre mémoire, & n’aïant pas perdû leur degré de chaleur par une froide recherche dans des siécles reculés, ils ne se présentent à nous qu’avec ces charmes, & cette importance que la verité & l’authenticité donnent aux moindres événemens.

Après avoir ainsi rendû justice à mon auteur, je serai plus concis sur ce qui me regarde moi-même & ma traduction. Je dois d’abord assurer le lecteur, que j’ai tâché de lui donner une idée exacte de l’original Persan, en le traduisant aussi literalement qu’il m’a été possible; en cela j’ai suivi & mes ordres & mon inclination. Nous avons asséz d’histoires Asiatiques habillées à l’Européene, j’ai laissé à celle-ci ses ornemens naturels: je n’ai orné aucun détail; j’ai suivi l’élévation ou l’abaissement du style, comme je les ai trouvés. Le peu de mots que je puis avoir ajoutés n’ont été que pour écarter des ambiguités attachées à la différence d’idiomes; je n’ai retranché que dans les endroits où les allusions étoient ou trop absurdes pour nous; que quand les expressions à force d’être outrées devenoient ridicules à l’imagination calme de nos climats. Si j’ai hazardé de donner une traduction rimée des vers que j’ai trouvé dans le corps de cette Histoire, j’en ai ajouté une litérale à la fin de chaque partie.

On trouvera dans mes Notes un index Géographique des principales villes & provinces dont cet ouvrage fait mention, mais j’ai été forcé de passer sous silence ce qui concerne plusieurs tribus, villages, & forteresses, dont on ne voit nulle trace dans les livres de géographie orientale que j’ai consulté.

Quant au traité sur la poésie Asiatique que j’ai ajouté à cette histoire, comme une espece de commentaire sur le goût poétique dans lequel élle est écrite, s’il s’y trouve quelques erreurs, j’en appelle au jugement impartial du lecteur savant; il considerera sans doute combien il étoit difficile d’entendre parfaitement des Odes dont le ton sublime & chargé d’ornemens embarrasse même ceux dans la langue desquels elles sont écrites, surtout étant privé du secours d’un bon commentaire, si nécessaire dans ces occasions. Au reste, comme il m’a été prescrit d’écrire cet ouvrage en François, j’espére qu’on excusera la témérité que j’ai eû en entreprenant une traduction si difficile dans une langue qui n’est pas ma langue naturelle. Je ne dirai pourtant point avec le Romain, qui publia un ouvrage Grec, que j’ai commis des fautes volontaires, afin quelles fissent connoitre quelle étoit ma patrie; au contraire, j’avoue que je n’ai rien oublié pour me mettre en état d’offrir un style correct; que j’ai reçû avec empressement tous les avis qui m’ont été donnés à ce sujet, & accepté avec reconnoissance les secours qui m’ont été offerts.

A Londres

1770. "

Translation in English:

" "This Work is not completely unfamiliar. An English author, in the pleasant

narratives of his journeys, mentioned a "life of Nader Shah", written in

Persian; but, he adds, that it is not very probable that it appeared

in Europe. Indeed, so that the public is enriched by this rare

present, the destiny should have made it land into the hands of a

Monarch who would have been very distinguished by his love for

beautiful Letters and delicacy of taste, what wasn't an easy happiness

to foresee. Loaded by the orders of this Monarch to translate it and

to publish this manuscript, I would like from my part to satisfy the

reader, by giving him a perfect knowledge of the author whom I

translate; but, my researches didn't lead me anywhere: the reader will

then have to content himself with my opinion."

I admit at first that

I'm not in the opinion of the author whom I have just quoted, who

announces my author as a general or a commander; it appears to me

rather a man of a deep knowledge, a pleasant eloquence and perfectly

comfortable in the oriental literature, as well as in the poetry of

his country. His notions on art of warfare, the way he describes the

battles are convenient by no means for a warrior, they agree much

better with the title of Mirza, which means man of education

(studies), when it precedes the proper noun; the title of Khan, which

is joined there, proves only that the knowledge, in Asia, is the road

to the fortune (happiness), as well as that of the glory. As this

story was written only twelve years ago, it is likely that Mirza

Mohammed Mahadi Khan of Manzanderan still lives, unless he died in

some danger similar to to those he describes, and which were so

frequent in his homeland in unfortunate time he deplores. However, the

narrative of the perpetual rebellions, often complicated, and renewed

once calmed, has something dry and tiring. The author felt it himself;

so, when he has no big and striking events to tell, he tries to make

the accuracy and even sometimes the darkness, bearable by his

fragments of Persian poetry as well chosen as placed. These essays of

oriental Rhetoric are overall admirable in the varied descriptions of

Spring, which he gives at the beginning of every year, and in which he

generally hints at what was the most remarkable that took place. This

work must naturally interest the public and attach the reader; the

facts are so recent, that they couldn't be erased of our memory and

not having lost their degree of heat because of a cold research of

past centuries, they appear at us only with their charm and the

importance that the truth and the authenticity give to the slightest

events.

After having so given justice to my author, I shall be more concise on

what is related to myself and my translation. I have to assure at

first the reader, that I've tried to give him an exact idea of the

original persian, by translating it as literally as I could; I have

followed my orders and my inclination. We have enough Asiatic stories

dressed in the European style, I left to this one its natural

ornaments: I decorated no detail; I followed the rise or the reduction

in the style, as I found them. The few words which I may have added

were only to spread ambiguities attached to the difference of idioms; I

deducted only in the places where the allusions were either too absurd

for us; or the outraged expressions became ridiculous in the

imagination of our climates. If I risked giving a translation put into

verse by the verses that that I found in the body of this story, I

added a literal at the end of each part.

We shall find in my Notes a Geographical index of the main cities and

provinces mentioned in this work, but I was forced to cross under

silence what concerns several tribes, villages, and fortresses, which

we have no track of in the oriental Geographical books I have

consulted.

As for the treaty on the Asiatic poetry which I added to this story,

as a kind of comment on the poetic taste in which it's written. If

there are some errors there, I call it to the imperial judgment of the

learned reader; he will consider doubtless how much it was difficult

to perfectly understand Odes with sublime tone and loaded with

ornements that embarrass even those who speak the language of the

author, especially being deprived of the help of a good comment, so

necessary in these occasions. Besides, as it was prescribed to me to

write this work in French, I hope that people shall excuse the

audacity which I've had by beginning a translation that difficult in a

language which is not even my mother tongue. Nevertheless, I won't

say with the Roman, who published a Greek work, that I committed

voluntary faults, so that they made know what was my homeland. On the

contrary, I admit that I haven't forgotten anything to enable me to

offer a correct style; that I have received obligingly all the notices

which were given to me on this subject, and accepted with thankfulness

the help which were offered to me. In London - 1770 "

Besides the French translation by Sir William Jones, the book was also translated into German by Röse Greifswald and into Georgian by David. These different editions of the book can be found in several Asian and European museums.

The English translation is available under this link: http://persian.packhum.org/persian/main?url=pf?file=14701010&ct=0

Mirza Mehdi Khan dedicated his History of Nader Shah to Mohammad Hassan Khan Qajar, the chieftain of the Qajar tribe, Agha Mohammad Shah’s father, and Karim Khan Zand’s greatest enemy. Here we can make an interpretation of what a great strategist he was: First, he first worked in the Safavid court. He then supported Nader Khan against the Afghans and became an important figure in the Afsharid court. Finally, he served in the Zand era, supporting the Qajars because he knew they were gaining power.

Mirza Mehdi Khan Esterabadi's work had a great impact on Persian literature. In "Iranian History and Politics The Dialectic of State and Society", Homa Katouzian writes "most parts of the Iranian cultural region were ruled by Turkic-speaking dynasties most of the time. At the same time, most of the chancellors, ministers and mandaring were Persian speakers of the highest learning and ability. To demonstrate this point, it should be sufficient just to mention the names of Maimandi, Baihaqi, Nezam-ol-Molk, Nasr al-Din Tusi, the brothers Shams al-Din and Ata Malek Jovaini, Rashid al-Din Fazlollah, Eskandar Monshi, Mahdi Esterabadi, the two Qa'emmaqams, Amir Kabir andt the two Mostowfi al-Mamaleks- starting with the Ghazvanid and ending with the Qajars."

Images from his book "History of Nader Shah"

References

1) Mirza Mehdi, for long years the doct Grand-Vezir of Nadir-iah of Persia (I736-I747), Analecta Orientalia Memoriae Alexandri Csoma de Koros dicata by Karl H. Menges

2) A cet effet il avait commencé par faire traduire en persan les quatre Evangiles ainsi que le Pentatenque. Mais son secrétaire Mirza Mehdi de Masandéran, qu'il en avait chargé, {...}, Nouvelle biographie générale depuis les temps les plus reculés jusqu'à nos jours, Hoefer

Nadir Shall, in 1740, ordered Mirza Mehdi to translate the four Gospels, The Cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern AsiaCommercial, by Edward Balfour

3) Tarikh Naderi, the History of the celebrated Tahmas Kuli Khan Nadrir Shah, written in the most refined language, by Vizir Mirza Mehdi Khan, Persian; well written, fol. in the original binding, {...} Waring enumerates it among the most admired-historical works in the language, Bookseller's catalogues by Howell

4) The circumstance took place which is here related from the history of Mirza Mehdi, who was his (Nader's) Vizier, Shreds and Patches of History by Routledge

5) "The "Nadernameh" is a Persian history, by Mirza Mehdi, who is stated by Sir J. Malcolm to have been confidential secretary of Nadir Shah, the History of India by Elphinstone

6) One of the earliest histories of Kashmir in Persian by an anonymous author.

Popular tradition believes his name to have been Mirza Mehdi, Kashmir series of texts and studies by University of Michigan

7) He is perhaps to be identified as Muhammad Mahdi-Khan Astarabadi, "friend and companion" of Nadir Shah , Peerless Images Persian Painting and its Sources, by Eleanor Sims

8) The Persian word mirza signified "Prince" when placed after the name, as here. When placed before the name it denoted a senior official or bureaucrat - Nader's particular secretary and official court historian Mirza Mahdi Astarabadi for example, the Sword of Persia by Axworthy

9) The Catholicos (a Christian visting Persia) later described Mirza Mahdi as a "wise, humble, polite, attentive, and respectable man, the Sword of Persia by Axworthy

10) Seven of Nader's closest advisers, including Tahmasp Khan Jalayer and Mirza Mahdi, had the nasaqchis bring groups of the delegates to them in succession, the Sword of Persia by Axworthy

11) [...] and they are less reliable for events further afield, for which it better in general to rely on Mohsen, Mirza Mahdi and Mohammad Kazem, one or more of whom were travelling with Nader most of the time, the Sword of Persia by Axworthy

12) L'Etat roule aujourd'hui sur deux personnages: le premier ministre, ou Itimad-eddaulah, qui a la direction de toutes choses liées à des relations étrangères; et commande les armées en l'absence du roi ou des princes, La Perse ou tableau de l'histoire du gouvernement de la religion by Amable Jourdain

Le premier personnage du royaume, après le roi, est l'Itimad-eddaulah, dont la dignité répond à celle du Grand-Visir chez les Turcs: c'est le premier ministre. Dans les suppliques qu'on lui présente, [...] ; mais on ne le désigne dans le langage familier, que par le nom d'Itimad-eddaulah, mot composé, qui signifie soutien de l'empire: ce ministre est en effet l'axe sur lequel tourne la masse énorme des affaires de l'Etat.Sa faveur est la seule voie pour obtenir des emplois et les bienfaits du prince; aucune demande ne parvient aux oreilles de la majesté royale, n'est exacuée, s'il ne la transmet, s'il ne l'appuie. [...] Les finances sont sous sa direction; [...]

13) The Vaziri family are the descendants of Mirza Mehdi Khan Etemadol-Dowleh Monshi Astarabadi, [...], Historical Geography and Comprehensive History of Kermanshahan by Mohammad-Ali Soltani

14) Placé devant le nom, c'est une épithète que chacun a le droit de prendre ou peut recevoir. Le premier ministre s'appelle Mirza-Séfi, l'historien de Nadir-Chah, Mirza-Méhdi, etc. Il est à remarquier néanmoins que les hommes instruits, ou qui suivent une carrière honorable, sont les seuls qui s'arrogent le titre de Mirza. La Perse ou tableau de l'histoire du gouvernement de la religion, by Amable Jourdain

15) In A History of Literary Criticism in Iran by Parsinejad, we can read a conversation between Reza Qoli Khan and Fath Ali Shah (his student) where the latter says In such circumstances your teacher Mirza Mahdi Khan Esterabadi writes{...}"

16) It is reported that on one occasion Mirza Mehdi was offered a bribe to intervene with the shah so he would renew the privileges of the Russia Company for trade with Persia: "He refused to take any action, and he was honest enough not to take the bribe." One of his contemporaries wrote that Mirza Mehdi was one of the three first-class persons in the time of Nader Shah. [...] The Armenian catholicos Abraham, who died in 1737, described Mirza Mehdi as "a wise, humble, polite, attentive and respectable man." According to an eighteenth century Armenian historian, Khatchatour Abegha Djoughayetsi, Mirza Mehdi was "a learned and wise man." It is apparent that Mirza Mehdi was a worthy scholar to supervise the Persian translation of the Bible and Quran and that he was a person greatly respected by the Christians. A Restless Search: A History of Persian Translations of the Bible, Kenneth J. Thomas, 2015

17) His name is Mirza Mohammad (i.e. Mirza Mohammad Naami Kermanshahi, please refer to Vaziri family genealogy) and his origins are from Esterabad. He is a descendant of Mirza Mehdi Khan the special secretary of Nader Shah. His father came to Kermanshah and he was born there. He is among the great poets of his generation and is responsible for the literature in Mohammad Ali Mirza Dowlatshah's government in Western Iran and Irak.{...} He died in 1818."

Sources

"History of Nader Shah" (Taarikhe Jahangoshaaye Naaderi), 1759, Mirza Mehdi Khan Esterabadi

"Historical Geography and Comprehensive History of Kermanshahan" (Tarikhe Mofassale Kermanshahan), 1994, Mohammad-Ali Soltani

"ASTARABADI, MIRZA (MOHAMMAD) MAHDI KHAN B. MOHAMMAD-NASSIR" in Encyclopaedia Iranica, by J.R. Perry

"Sword of Persia" by Michael Axworthy

"The Cambridge History of Iran" by P. Avery, G. R. G. Hambly and C. Melville

http://www.salarsolmaz.blogfa.com/post-7.aspx